Luxating Patella In Dogs

In-home rehabilitation to improve stifle stability, correct gait, and support long-term mobility

Understanding Luxating Patella In Dogs

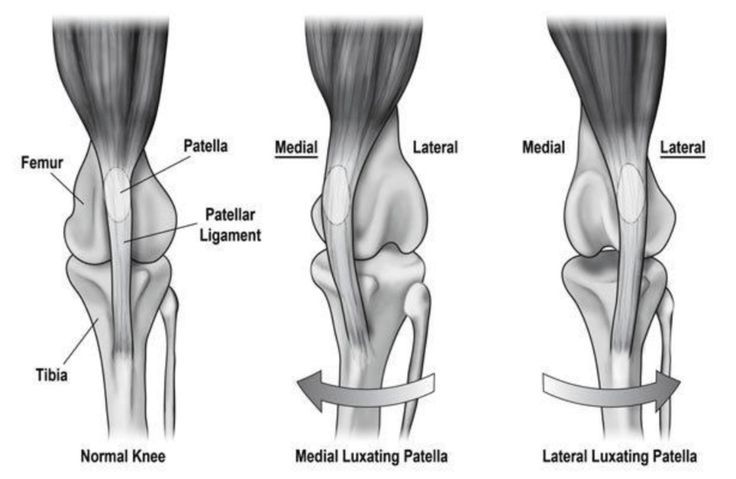

Luxating patella in dogs refers to a condition in which the kneecap (patella) dislocates or “pops out” of its normal alignment within the femoral groove. This occurs most commonly in small and toy breeds but can affect dogs of any size. Medial patellar luxation (MPL) is more prevalent than lateral luxation, and severity can vary from intermittent dislocation with minimal discomfort to persistent luxation causing chronic pain, lameness, and structural changes to the stifle joint.

Underlying causes often include a shallow trochlear groove, femorotibial misalignment, rotational limb deformities, and soft tissue imbalance. Over time, luxating patella in dogs may lead to cartilage wear, inflammation, muscle asymmetry, and degenerative joint changes if left untreated.

Clinical signs range from occasional skipping or hindlimb “hitching,” to more consistent lameness, pain, or reluctance to bear weight on the affected limb. Early recognition and management are key to reducing long-term joint damage.

Clinical Signs of Luxating Patella in Dogs?

Clinical signs of luxating patella in dogs can vary widely depending on the severity of the condition. Some dogs may display only subtle changes, such as occasional skipping or a “hopping” gait in the hindlimb, while others develop intermittent lameness, limb weakness, or more persistent signs of joint dysfunction. In advanced cases, dogs may show reluctance to bear weight on the affected limb, evident discomfort during movement, and visible muscle atrophy due to disuse and reduced mobility.

Patellar luxation is graded based on the degree of dislocation and how easily the patella returns to its anatomical position:

-

Grade 1: The patella resides in the trochlear groove but can be manually luxated. It rarely dislocates spontaneously and immediately returns to its normal position upon release.

-

Grade 2: The patella remains within the trochlear groove but can spontaneously luxate during limb movement or manipulation. It typically returns to position either with manual correction or when the limb is extended.

-

Grade 3: The patella is frequently dislocated and remains outside the trochlear groove. It can be manually repositioned but does not stay in place.

-

Grade 4: The patella is permanently dislocated and cannot be manually returned to its correct anatomical position due to structural changes in the joint.

Treatment for luxating patella in dogs depends on the grade and clinical presentation.

-

Grades 1 and 2 are often managed conservatively through a combination of manual therapy, therapeutic exercise, weight management, and medical pain control.

-

Grades 3 and 4 typically require surgical intervention to realign the patella and stabilise the joint, followed by structured rehabilitation to restore function and reduce the risk of recurrence.

Why Early Rehabilitation Matters

In both conservatively managed and post-surgical cases, early rehabilitation plays a critical role in improving stifle mechanics, reducing discomfort, and preventing compensatory issues. When the patella does not track properly, it affects the overall biomechanics of the limb—placing excess strain on surrounding musculature and adjacent joints, particularly the hips, spine, and contralateral hindlimb.

Rehabilitation helps restore quadriceps symmetry, strengthen stabilising structures, and retrain proper limb use before chronic patterns of asymmetry and disuse are established. Neuromuscular re-education is essential for re-establishing motor control of the limb and promoting more accurate patellar tracking. In dogs recovering from surgical patellar stabilisation, structured therapy helps reduce inflammation, maintain range of motion, and rebuild strength safely during each phase of healing.

Timely intervention reduces the risk of secondary joint stress, delays degenerative changes, and supports a smoother return to functional movement.